To Prevent Rheumatoid Arthritis, Look Past the Joints to the Gums

Jennifer Abbasi Article Information JAMA. Published online March 8, 2017. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.0764

The mouth may seem like a strange place to search for a culprit in a disease that primarily affects the joints. But a recent collaboration by a group of multidisciplinary researchers suggests that one type of oral bacteria may be an important trigger in about half of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) cases.

The findings, published in Science Translational Medicine late last year, appear to confirm something that’s been suspected for at least a century: In some cases, gum-disease causing oral bacteria may set off a cascade of events that leads to the autoimmune form of arthritis.

It’s long been known that patients with RA are more likely to have periodontitis. In 1 nationally representative sample, participants who met 4 out of 6 American College of Rheumatology criteria for RA had a 4-fold higher risk of periodontitis compared with those who didn’t meet that threshold.

In both conditions, chronic inflammation destroys hard tissue teeth-bearing bone in periodontitis and the joints in RA. Researchers have implicated several species of bacteria in gum disease, but what causes RA is still a mystery. Because periodontitis and RA often go hand in hand, researchers suspect that oral bacteria could be involved in RA.

To pinpoint the right bug, investigators have been searching for an oral microbe that can trigger the production of autoantibodies seen in patients with RA, said Maximilian F. Konig, MD, lead author of the new study and resident physician at Massachusetts General Hospital. Konig’s study, conducted when he was a postdoctoral fellow at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, has moved the field closer to that goal.

The most accurate marker for RA found in the blood of 76% of RA patients is anticitrullinated protein antibodies (ACPAs). These autoantibodies target citrullinated proteins that are expressed by immune cells such as neutrophils.

Citrullination is a normal process that changes the structure of proteins, altering their function. Felipe Andrade, MD, PhD, senior author of the study and associate professor of medicine in the division of rheumatology at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, likened citrullination to small costume changes the addition of a moustache or a hat, for example. These changes cast proteins into new roles. “[How] you’re dressed defines your function,” he explained.

These protein modifications are necessary, and they usually fly under the radar of the immune system. But too many of them can raise alarm bells.

In patients with RA, hypercitrullination, an abnormal build-up of citrullinated proteins, triggers the immune system to generate autoantibodies that attack these modified self-proteins, inducing joint-destroying inflammation.

Konig, Andrade, and their coinvestigators found a mouth bug with a tongue-twisting name, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (Aa), can cause these runaway protein changes and drive RA-specific autoantibody production, key steps in the path to RA.

Dagmar’s comment: as proteins are most frequently the culprit in many allergy-type reactions, taking the above research to another level – perhaps we should consider oral health in many chronic, unresponsive allergic conditions.

For U.S. readers, here is a link for anti-inflammatory support: https://www.cognitune.com/turmeric-curcumin-benefits/

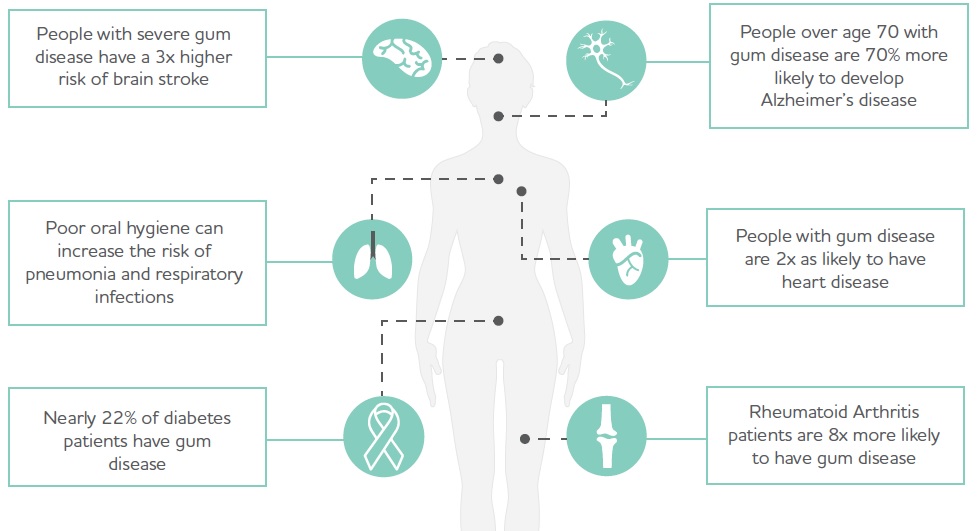

Oral dysbiosis is linked to an increased risk of numerous other diseases:

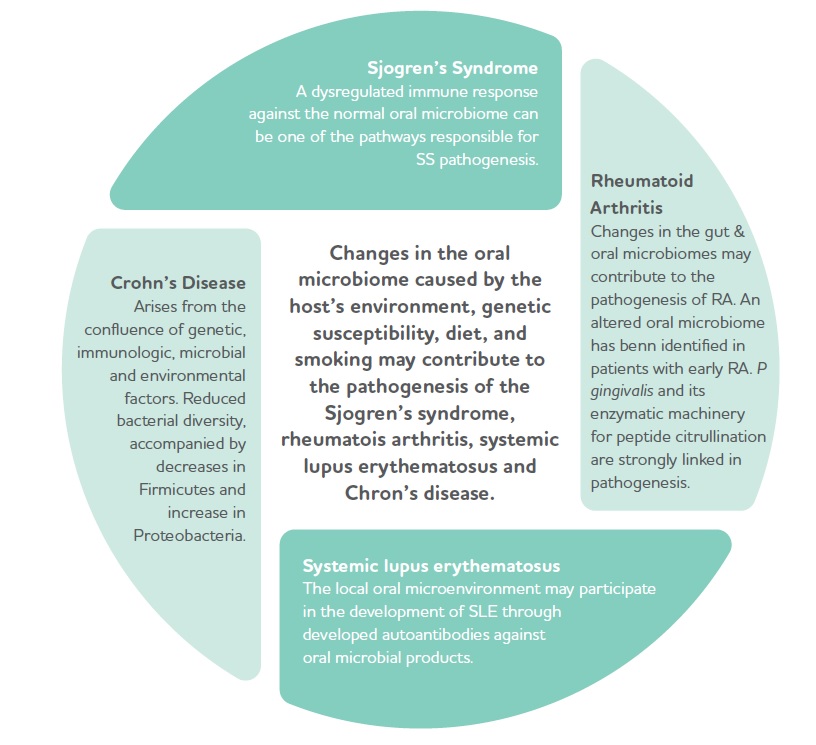

Changes in oral microbial balances are linked to autoimmunity